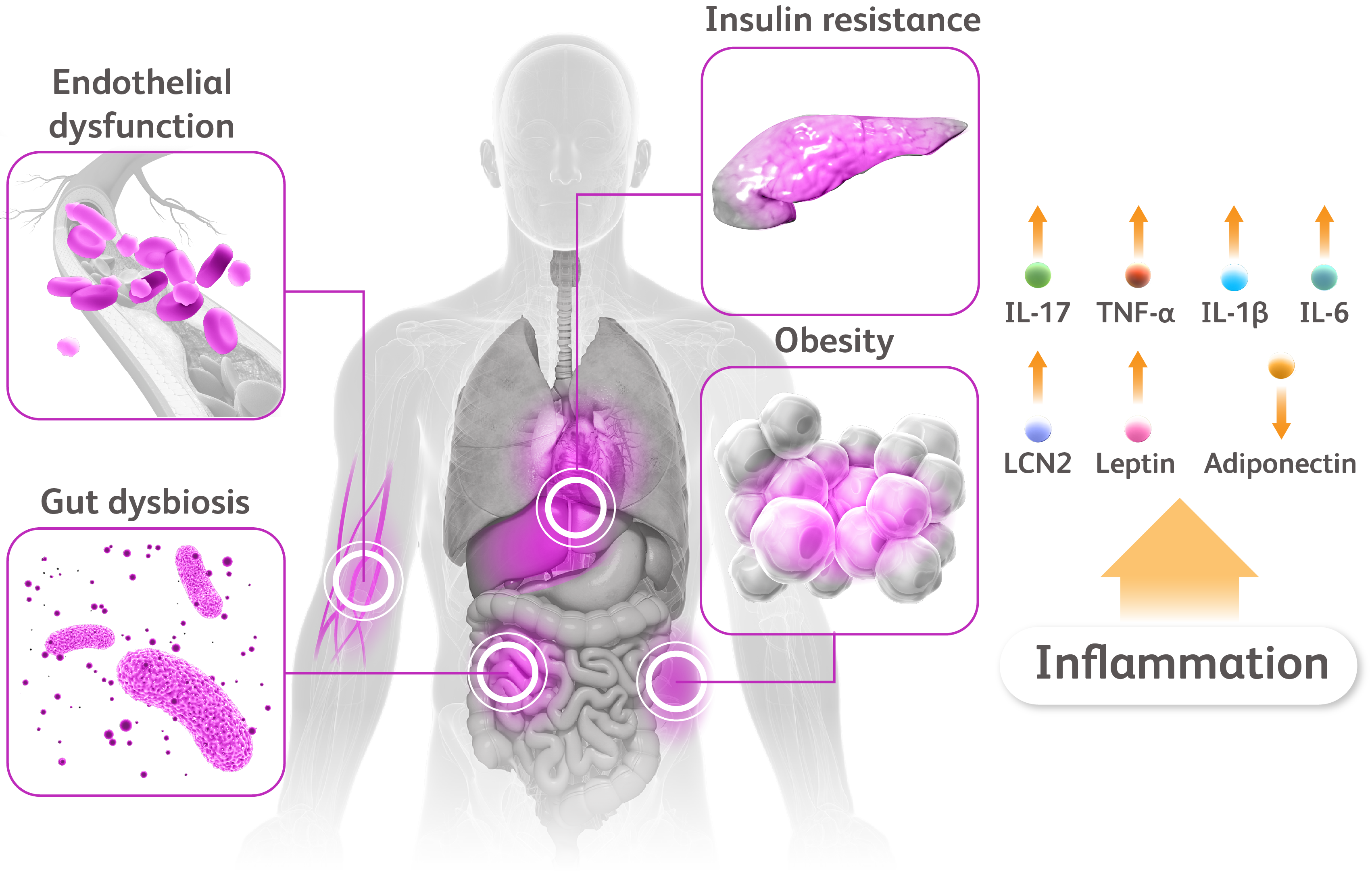

more than a skin disease

References

- Gisondi P et al. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:21–28.

- Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073–1113.

- Armstrong AW et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:654–662.

- Armstrong AW et al. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:e54.

- Armstrong AW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:84–91.

- Azfar RS et al. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:995–1000.

- Merola JF et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1495–1500.

- Gisondi P et al. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1754–1757.

- Arnett DK et al. Circulation. 2019;140:e596–e646.

- Hao Y et al. Front Immunol. 2021;12:711060.

- Kong Y et al. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18:171.

- Coimbra S et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1386–1394.

- Lockshin B et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:345–352.

- Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. Clin Immunol. 2020;214:108397.

- Wu JJ et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18044.

- Wang Y et al. Clin Chem. 2007;53(1):34–41.

- Wang D et al. Disease Markers. 2019;7361826:1–19.